Learn faster by slowing down

Reflection on 4 years of ineffective self-study and the solutions I found.

This edition took a long time to release due to weeks of reviewing and sorting everything I’ve ever written.

With it fresh on my mind, there’s nothing else I could bother writing writing about, so here’s my experience.

4 years since dropping out of college, I’ve had the conviction that I’ll do it on my own, become a lifelong scholar, and end up as the poster-boy for self-improvement.

Before I signed the lease for my mountain residence to be a local wisdom peddler, I open my journal to reflect on the wonders of the great knowledge I have accumulated and..

Well, my dream of being a great scholar isn’t going anywhere. I have nothing to show for it.

It’s a nightmare. What have I been doing all this time?

I had done SO much work on myself. I crushed journal pages, videos and courses, bestselling books everyone else has read. I’m supposed to be on track to enlightenment and shooting lasers of positivity out of my eyes.

(as advertised in the bestsellers).

All I wanted 4 years ago was to improve myself. I didn’t know what I wanted, I just knew I needed.. better. I hurried out in every direction I could to make progress in different areas in my life that other people told me was “the most important thing.”

And the result?

I became a tourist.

Blitzing through different content attractions. Self-help guru’s guiding me to the good-life. I checked off books and videos like they were countries I could mark on a travel log and pretend I knew all about it. I felt with each discovery — my inner world must be evolving.

Not quite.

Most of those discoveries lie dead in a notebook.

Forgotten

Unused

Useless

Added to the stack so I could show everyone how great I’m doing as an explorer.

Silly tourist.

Seeing the museums, buildings, and wonders of a new place doesn’t mean you can “mark it off.” Your selfie with the Sagrada Familia doesn’t mean you “get” Barcelona.

You’ve been there, great. What of it? What does it mean to you?

Every time I found something else, I had a new hit. A bump of philosophical clarity.

I became a learning junkie, addicted to novel ideas.

The only thing I brought back from my tours through instagram and self-help books were souvenirs of digital junk.

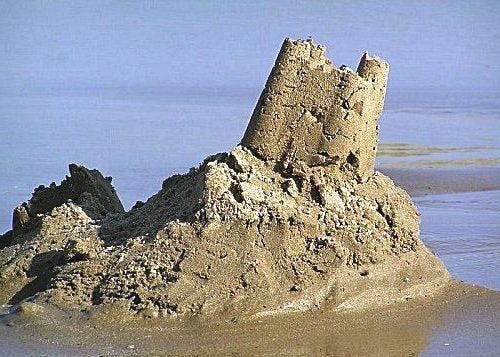

But now, I’m face to face with that junk, and the wonderful palace of knowledge I was building looks more like a sandcastle that’s been through high tide.

What did I do wrong?

In hindsight, I’m grateful for the initial scrambling. You need a sandbox period to learn the basics before you add structure. This helped me figure out how to be discerning with what I consume and how to approach learning.

What I did wrong was staying in this sandbox expecting it would work as a foundation.

If you’re going to build something worthwhile, you need good structure under it, not sand.

I want to use what I learn instead of letting it slip through my fingers. Despite being familiar and with a ton of ideas, everything was shallow.

I didn’t have depth in my understanding of these ideas.

So, tired of knowing-about things I decided to finally know them.

In steps this will look like:

Capture

Organize

Cement (structure + process)

Feedback

What is capture?

At best: We’re taking needles out of the haystack and putting them into their own pile.

At worst: We become hoarders

In my case, well take a guess.

In 4 years I filled hundreds of pages in my journals, took tons of screenshots of posts and quotes on the internet, and created mountains of notes on my phone (1,594 of them to be exact).

The great collector of ideas — this is what I found when I finally cleaned out the closet.

Apple Notes:

95% of notes I never looked at again.

I made dozens of 2-5x repeated notes on the same ideas.

Many were barely legible to myself and certainly not anyone else.

Tons of reminders and quick mark downs for later (which, I never reviewed).

The ones I thought were “profound” were too loose. Trying to connect multiple ideas and getting off track (They couldn’t stand on their own).

Starting my new system, I transferred ~1200 of those notes and only kept 300. Most of them are reference for stories in my personal life. Only 80 made it as ideas worth keeping (after some serious editing).

My capture hasn’t changed a ton, (The biggest benefit is the steps AFTER capture that compound learning) but we need this to start.

Here’s what I do:

Phone is quick capture. Jot down nagging thoughts to stop them from looping.

Highlights and notes in books.

Save website links for blogs or newsletters.

The journal captures the reference material for your life. External and internal.

Use the journal as a place for commentary, thoughts and opinions and a canvas to wrestle with your beliefs. If you can observe and sort through all the racket in your head it will reveal who you are. This is the best tool for spiritual learning.

The keys to good capture:

If you don’t capture, it’s lost. When you do capture, use it quick.

Not all sources are equal. Ideas in books undergo more scrutiny by the author than their social media posts.

Don’t capture just because you feel like you should. Trust your instinct — if it doesn’t interest you don’t waste time on it.

If you’re directly saving something, don’t leave it as is. Write along with it. “This made me think about X. This can help me with Y. This is interesting because Z.”

The danger here is how addicting this step can be. Knowing about things feels rewarding but it is not understanding. All we’re doing is collecting raw material.

Just remember the tourist (never achieving depth)

We need to avoid the addiction cycle of novelty and push deeper.

2. Organize

Organization doesn’t technically help you learn ideas, but it will be important as you continue learning. You’ll need to navigate what you’ve captured so you can review and re-work notes.

I honestly don’t have much to say here, I’m still figuring it out myself.

Don’t be afraid to change it up—organization always seems to work at first.. until it doesn’t.

The more information you’re working with the more complex it gets. I don’t think it will ever feel perfect.

The best thing I can say is link your notes. If what you’re writing reminds you of another idea, link them together so they’re not stuck in whatever file you threw them into (like how wikipedia is a ton of embedded links).

(I’m not actually sure if most note-taking software allows for this. I use obsidian because of it and even though it’s the inspiration for this edition, it’s a whole can of worms that I will have to get into another day)

That’s all I got.

3. Cement

If capture is passive collection; this step is active engagement.

We’re going to expend some effort — but if you follow through, your understanding will surpass 95% of people.

You know the cement trucks with the big spinning cylinder at the back?

That’s all the stuff we captured. It’s tumbling around up there with all the other things you think about. Right now it’s junk. Wet sand.

We’re going to turn the raw material into a fundamental unit of knowledge.

The atomic note.

What’s the structure of an atomic note?

You don’t pour cement straight on the ground, you plot it first (square sidewalks). Within these boundaries is where we are going to pour the idea onto the note.

That’s the target for our final product.

For example: Niklas Luhmann, (the guy who pioneered this and one of the most productive academics of all time within his field) wrote all his notes on index cards.

This forced him to be concise with his ideas. If you can’t fit an idea into a paragraph or handful of sentences, chances are you don’t know it well enough — or the topic is too broad.

The key is to narrow down our topics. On a laptop I aim for not having to scroll to see the whole page.

It requires a good grasp on an idea to constrain it to the limits we set. If we can’t fit it, we need to continue putting pressure on our thinking until we can.

Get the picture? Sweet.

That’s how it will look—but the process is even more important.

What’s the process?

If the structure of our atomic note is the plot; Articulating the idea in writing is funneling the cement.

Using your own words; Summarize the idea

I know, I sound like an annoying english teacher. I promise there’s good reason for it.

When we copy, we’re not doing our own thinking.

Copying takes us straight to the answers. We can repeat them without knowing how we got there or why it’s correct. This leads to flimsy understanding in the long run. The kind of stuff you write on a test but won’t be able to recognize if it slapped you in the face in the real world.

The person who says he knows what he thinks but cannot express it does not know what he thinks. - Mortimer Adler

What matters is being able to show our work. Not because it makes your teacher happy or to impress anyone else—but because we owe it to ourselves. The good thing is, you decide how your work is shown.

If you’re not able to do it right away that’s okay. When I first started journaling it blew my mind seeing how much I didn’t know because I couldn’t write clearly.

I used to think I understood an idea when I copied it down — but once I’m familiar with an idea I found I typically need 2-3 sources (or personal experience for certain topics) and some review before I’m happy with the final draft of my note.

Now that you’ve poured the cement we need to smooth it out. If it’s spreading too far remove the excess. If it’s missing some spots, fill it in.

This is the point when your idea goes from a rough shape into a beautiful note. You’ll be proud of what you make.

When writing is clear, it’s because of pure genius. lots of editing.

Don’t underestimate how much better you can make a piece of writing simply by coming back to work on it a few times.

Which brings me to our final step.

4. Feedback

If how you learn is anything like what I did for years—Feedback is the wave that comes crashing in and washes away your sandcastle.

How wonderful.

Feedback stress-tests our thinking.

When we perform skills, test our theories, and live our philosophy—we accumulate valuable feedback in the forms of criticism, decisions we make, and other results reflecting how we think.

Now we can iterate and adjust what we already have to make it better.

So how do we use it?

We need to communicate our ideas to open them up for feedback:

Talk about it with friends.

Privately share what you’ve written.

Teach someone what you’re learning.

(Post about it on Substack ;))

Richard Feynman (a nobel prize winner) was widely known as Physic’s best teacher. He was famous for breaking down intricate ideas down for students of any level—he saw teaching as a necessary part of learning.

“If you want to master something, teach it.”

R. Feynman

Teaching is the perfect feedback because it requires a deep understanding of your topic to transfer it to someone else.

If another person finds it difficult to follow, chances are you’re not being clear enough.

Make it simple—try to explain the idea without complex language.

If you aren’t at a level to teach it well, start a conversation with someone else familiar with the idea, explore and build upon your understanding by asking questions.

The point here is we want to see how robust your thinking is, everyone is going to find gaps, fall prey to fallacies and inconsistencies, and be flat out confused at times.

Feedback exposes our gaps so we can restart the process and make it stronger the next time.

Key point to remember:

The shorter your feedback loops—the more accelerated your learning will become.

Quick Review

Now that we’ve seen the full picture, it’s easier to recognize how each step is going to play into each other.

Capture:

Mark down, record, and swipe anything we find useful. Quality is good here but we don’t need to be too discerning.

Organize:

Put it where you’ll be able to find it later, this will mostly matter for the atomic notes we make because we’ll want them all in one spot and easy to access.

Cement:

Atomic notes are trying to capture the concept. When we understand the concept of an idea we will recognize it regardless of the context we find it in.

Tortoise and the Hare? Consistency beats intensity.

“You catch more flies with honey than vinegar” (It’s more useful to be nice than critical).

We still want to take notes from sources, but we need to make atomic notes out of the specific concepts we find most important to us.

We’re going to integrate the concept by using our own words.

The more we encounter this concept the more we can test our original note.

Simple and clear is the best sign that we’re doing it right.

A great atomic note worked on over time will cement the concept into your head.

Feedback:

Stress test our ideas by putting it out there.

This will test your own knowledge and show you the gaps.

If you can’t teach it, you probably don’t understand it well enough.

In closing

When I was stuck in tourism, I skated around capturing everything before I could sit down and cement the ideas into my head. I just wanted to chase the shiny things because I overvalued novelty—feedback exposed the weight of those “ideas” to me.

The 800+ notes I deleted all seemed important at the time—but they turned out to be feathers which hardly counted for anything.

The surviving notes and ones I create today are what I reference in conversation, use in my own life to make better decisions, and insights which keep me on the path I want to pursue.

Editing and working on the heavy concepts with much more depth is how I’m choosing to deepen my relationship with the most important ideas in my life.

To take a step back and look at the bigger picture,

The entire reason I learn is the hope that I can change my behavior.

Of course, I still take joy and allow things to be done for their own sake. Not everything has to be obsessive, that’s just the kind of person I am.

Education has an incredible benefit on our lives—but we need to personalize it.

If I knew what I was about to try and “learn” from would have zero impact on my behavior, I wouldn’t bother with it.

So before we get caught up and mistake real education for tourism and entertainment, ask yourself:

“How am I going to change by learning this?”

Knowledge alone is not power. It is potential—and only when we use it does it become power.

Thanks for reading.

I hope this was helpful.

Until next time,

Keaton

P.S. Obsidian is the powerhouse tool that solved all of my study issues. It has allowed me to learn way more effectively using all of the steps I wrote here.

I boiled it down because it these steps are the actual work, and I wanted this accessible even if you don’t want to use it.

It is worth noting though, that there are greater benefits (including organization) which I decided to leave out because I didn’t want to get too exhaustive or make this about obsidian.

We’ll come back to it later for a full post—but if you are interested you can watch the guide for the system I first set up here.